Current Sociology

http://csi.sagepub.com/

From sex roles to gender structure

Barbara J Risman and Georgiann Davis

Current Sociology 2013 61: 733 originally published online 12 March 2013

DOI: 10.1177/0011392113479315

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://csi.sagepub.com/content/61/5-6/733

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

International Sociological Association

Additional services and information for Current Sociology can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://csi.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://csi.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Aug 19, 2013

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Jul 2, 2013

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Mar 22, 2013

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Mar 22, 2013

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Mar 12, 2013

What is This?

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on October 20, 2013

479315

2013

CSI615-610.1177/0011392113479315Current Sociology ReviewRisman and Davis

Current Sociology Review Article

From sex roles to gender

structure

CS

Current Sociology Review

61(5-6) 733­–755

© The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0011392113479315

csi.sagepub.com

Barbara J Risman

University of Illinois at Chicago, USA

Georgiann Davis

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, USA

Abstract

This article has two goals, an intellectual history of gender as a concept and to outline

a framework for moving forward theory and research on gender conceptualized as

a structure of social stratification. The authors’ first goal is to trace the conceptual

development of the study of sex and gender throughout the 20th century to now. They

do this from a feminist sociological standpoint, framing the question with particular

concern for power and inequality. The authors use a modernist perspective, showing

how theory and research built in a cumulative fashion, with empirical studies sometimes

supporting and sometimes challenging current theories, often leads to new ones. The

authors then offer their theoretical contribution, framing gender as a social structure as a

means to integrate the wide variety of empirical research findings on causal explanations

for and consequences of gender. This framework includes attention to: the differences

and similarities between women and men as individuals, the stability of and changing

expectations we hold for each sex during social interaction, and the mechanisms by

which gender is embedded into the logic of social institutions and organizations. At each

level of analysis, there is a focus on the organization of social life and the cultural logics

that accompany such patterns.

Keywords

Gender, gender structure, sex, stratification

Corresponding author:

Barbara J Risman, University of Illinois at Chicago, MC 312, 1007 West Harrison Street, Chicago, IL 60607,

USA.

Email: brisman@uic.edu

734

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

The study of sex and gender is now such a vibrant field of inquiry in the social sciences

that it is easy to forget how recently research and theory on the topic was rare. At the start

of the 20th century, psychoanalysis was the state of the art, and the Electra and Oedipal

complexes presumed to account for sex differences. Much has changed since then. In this

article, we offer an intellectual history of scientific research and theory about gender,

with particular although not exclusive attention to traditions developed in the North

American context. We start with a brief overview of the evolution of biological theories

that help explain sex differences. We then discuss how psychological theories built upon

research findings to sharpen the conceptualization of gender as a personality trait

throughout the 20th century. We focus most attention on dueling theories, and subsequent integrative ones within sociology. Here too, we argue that theoretical arguments

framed research that often refuted the theory itself, thus spawning new research traditions. We discuss how sociology of gender has followed a normative scientific model as

it has developed over time, with theories tested by research, and reformulated based on

evidence. Research findings have led to new theoretical formulations. In the conclusion,

we argue for the efficacy of using Risman’s (1998, 2004) conceptualization of gender as

a social stratification structure with consequences for individual selves, interactional

expectations of others, and embedded in organizations because it helps to organize and

advance research, analysis, and social justice projects.

The birth and evolution of biological theories for sex

difference

Endocrinologists, medical doctors with expertise on the production, maintenance, and

regulation of hormones, have long believed masculinity and femininity were the result of

sex hormones (Lillie, 1939). William Blair Bell, a British gynecologist, first made this

explicit in 1916 when he wrote ‘the normal psychology of every woman is dependent

on the state of her internal secretions, and … unless driven by force of circumstances –

economic and social – she will have no inherent wish to leave her normal sphere of

action’ (1916: 129). Gendered behaviors began to be justified by sex hormones, rather

than religion (Bem, 1993). Further research discovered that the existence of sex hormones did not distinguish male from female, but rather both sexes showed evidence of

estrogen and testosterone (Evans, 1939; Frank, 1929; Laqueur et al., 1927; Parkes, 1938;

Siebke, 1931; Zondek, 1934a, 1934b). It became clear that estrogen and testosterone not

only affected reproduction and sex but also other aspects of the body including, but not

limited to, the liver, bones, and heart (David et al., 1934). The possibility that sex hormones

directly caused sex differences began to be suspect.

In 1965, Young et al. suggested that sex hormones during gestation create brain differentiation, and thus were indirect causal agents for sex differences (Young et al., 1965;

see also Phoenix et al., 1959). Young et al. wrote, ‘The realization that the nature of the

latent behavior brought to expression by gonadal hormones depends largely on the character of the soma or substrate on which the hormones act. The substrate was assumed to

be neural’ (1965: 179). This was quite a provocative claim when it was made, as it classified the brain as involved in reproductive functions. The brain began to be seen as responsible for sexual differentiation, as well as sexual orientation and gendered behaviors

(Phoenix et al., 1959).

Risman and Davis

735

Although arguments about brain sex first originated in the late 1950s and early 1960s

(Phoenix et al., 1959; Young et al., 1965), there has recently been a resurgence of such

research (Arnold and Gorski, 1984; Brizendine, 2006; Cahill, 2003; Collaer and Hines,

1995; Cooke et al., 1998; Holterhus et al., 2009; Lippa, 2005). Cooke et al.’s (1998)

review article concluded that ‘there is ample evidence of sexual dimorphism in the

human brain, as sex differences in behavior would require, but there has not yet been any

definitive proof that steroids acting early in development directly masculinize the human

brain’ (quoted in Diamond, 2009: 625). Hrabovszky and Hutson (2002) and Collaer and

Hines (1995) claim prenatal androgen exposure is strongly correlated with postnatal sextypical behavior. Juntti et al. (2008) have more recently argued that, at least for mice, sex

hormones are capable of controlling gender-specific behavior. In other words, contemporary brain sex theories continue to be centered on how sex hormones in utero shape brain

function. Brain sex theories of the 21st century maintain that brains are the intervening

link between sex hormones and gendered behavior. Some sociological research (Rossi,

1983; Udry, 2000) presumes that biological sex differences interact with cultural experiences to exacerbate or diminish sex differences. There has been little concern with inequality between women and men in this research tradition. Rather, the goal has been to

isolate biological contributions to sex difference.

Research on sex differentiated brains is not without its critics (Epstein, 1996; FaustoSterling, 2000; Jordan-Young, 2010; Oudshoorn, 1994). For example, Jordan-Young

(2010) conducted a synthetic analysis of over 300 brain sex studies and interviews with

scientists who conducted them. She concludes that brain organization research does not

pass the basic litmus tests for scientific research: they are so methodologically flawed as

to produce invalid results, as they rely on inconsistent conceptualizations of ‘sex,’ gender,

and hormones. When conceptualizations of one study are applied onto another, findings

are not usually replicated. The major deficiency of brain theories of sex differences is that

there are few consistent results across studies, they also depend on inconsistent definitions

and measurement of concepts, and so lack reliability as well. This research continues

albeit mostly in the form of animal research or quasi experimental data about human

beings. Nevertheless, research continues and social scientists only rarely test their theories

against biological ones (see an important exception in Udry [2000] and the critical

responses that followed: Kennelly et al., 2001; Miller and Costello, 2001; Risman, 2001).

The birth and evolution of social science attention to

sex and gender

Few social scientists were concerned with issues of sex and gender before the middle of

the 20th century. The field has literally exploded in the last several decades. Today, the

Sex and Gender section of the American Sociological Association is one of the largest

sections of the organization, and in 2013, both ASA President and Vice-President are

self-identified feminist scholars who write about gender, Cecilia Ridgeway and Jennifer

Glass. In this section, we present a brief social history of the fast and furious development of social scientific thought on sex and gender.

We argue that during the heyday of functionalist sociology, family sociologists (e.g.,

Parsons and Bales, 1955; Zelditch, 1955) were those primarily interested in sex and gender and wrote about women as the ‘heart’ of families with male ‘heads.’ Psychologists

736

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

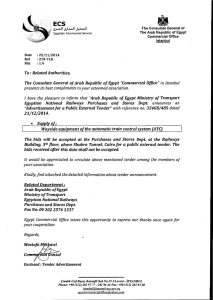

Figure 1. Unidimensional measure of gender.

(Bandura and Waters, 1963; Kohlberg, 1966) used socialization theory to explain how

girls and boys became socially appropriate men and women, husbands and wives. Little

research or theoretical writing focused on sex or gender, and almost none on inequality

between women and men (Ferree and Hall, 1996). This changed as women entered the

academy (England et al., 2007). We choose to highlight in this article the research traditions that we identify as having been the intellectual foremothers of where we are today.

The psychological measurement of sex roles

Serious attempts to study sex and gender followed the movement of women into science,

and the influence of the second wave of feminism on intellectual questions. Psychologists

(e.g., Bem, 1981; Spence et al., 1975a) began to measure sex role attitudes using scales

that had been embedded in personality and employment tests (Terman and Miles, 1936).

These measures implicitly assumed that masculinity and femininity were opposite ends

of one dimension (see Figure 1), and thus if a subject was ‘high’ on femininity, she was

necessarily, by measurement design, ‘low’ on masculinity.

Research began to suggest, however, that measurement itself was creating meanings

that did not accurately reflect individual personality traits (Edwards and Ashworth, 1977;

Locksley and Colten, 1979; Pedhazur and Tetenbaum, 1979). The research evidence led

Bem (1981, 1993) to offer a new conceptualization of gender that has become the gold

standard in the social sciences, now so taken-for-granted that she is no longer even cited

with the innovation. Bem suggested that masculinity and femininity were actually two

different personality dimensions (see Figure 2). For example, an individual could be high

on masculinity and also high on femininity or low on both masculinity and femininity.

Traditional women would be high on femininity and low on masculinity, and traditional

men would be high on masculinity and low on femininity. An aggressive and agentic

woman might be low on femininity and high on masculinity, or high on both masculinity

and femininity.

A decade of debate ensued on the best use of and measurement for this new conceptualization (Bem, 1974, 1981; Spence et al., 1975a, 1975b). Particular controversy

focused on whether the label ‘androgyny’ should be defined by similarity on both measures or only strong identification with both masculinity and femininity, with the consensus emerging that only those high on both should be labeled androgynous (Bem, 1974,

1993; Taylor and Hall, 1982; White, 1979) (see Figure 3).

The most recent writing in this tradition (Choi and Fuqua, 2003; Choi et al., 2008;

Hoffman and Borders, 2001) suggests that psychologists no longer find the language of

masculinity and femininity useful, but rather suggest that the personality concepts in the

Risman and Davis

737

Figure 2. Masculinity and femininity as independent measures.

Figure 3. Gender as personality trait, sex role inventory.

scale labeled ‘masculine’ actually measure efficacy/agency/leadership and the personality concepts in the scale labeled ‘feminine’ actually measure nurturance and empathy

(see Gill et al., [1987] for the first formulation of this rhetorical critique). While we agree

this linguistic change is the best trajectory for the future, we continue to use the language

of masculinity and femininity here when discussing research about individuals because

that is the rhetoric in the literatures we are reviewing.

Sociological evolution from sex roles to gender

When sociologists turned serious attention to sex and gender, they too focused on the

differences between individual women and men rooted in childhood sex role socialization (Stockard and Johnson, 1980; Weitzman, 1979). They studied how babies assigned

to the male category are encouraged to engage in masculine behaviors, offered boyappropriate toys, rewarded for playing with them, and punished for acting in girlish

ways, while babies assigned to the female category are encouraged to engage in feminine

behaviors while being limited to girl-appropriate toys such as dolls and easy bake ovens

(Weitzman et al., 1972). Sex role socialization theory maintains that children are accordingly rewarded for displaying the gender-appropriate behaviors that they are encouraged

to perform. The result of endemic socialization is what creates the illusion that gender is

naturally occurring. This differed from earlier versions of sex role socialization and functionalist family sociology with its critical edge, presuming that female socialization disadvantaged girls (Lever, 1974).

Lopata and Thorne (1978) published a path breaking now iconic article in which they

argued that sociologists were ignoring the functionalist presumptions and empirically

problematic evidence when they used ‘sex role’ explanations for gender differences.

They suggested that the very rhetorical use of the language of ‘role’ requires conceptualizing a functional complementarity void of questions of power and privilege. Lopata and

738

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

Figure 4. Sociological alternatives.

Thorne suggested that social scientists would rarely, if ever, use the language of ‘race

roles’ to explain the differential opportunities and constraints of majority and minority

members of a western society. More empirically substantive problems existed as well.

The language of ‘sex role’ presumed a stability of behavior expected of women (or men)

across their social contexts, their life-cycles, and whatever culture or sub-culture they

might enter (see Connell, 1987; Ferree, 1990; Lorber, 1994; Risman, 1998, 2004).

Lorber’s exhaustive review of gender research in the 20th century showed that a role conceptualization was inaccurate and also that limiting a sociological understanding of gender to personality was inadequate. Chafetz (1998) argued that in a North American

context, where students were so individualist that they were ready to assume all behavior

freely chosen, we should ban the world ‘socialization’ from the classroom until other

avenues of explanations for gender inequality had been explored. While that may have

been an extreme position, the die was cast, as sociologists began to explore gender beyond

its definition as a personality trait. Kimmel (2008: 106) summarizes a widely held contemporary position when he writes that ‘sex role theory overemphasizes the developmental decisiveness of early childhood as the moment that gender socialization happens.’ With

such critiques of sex role theory, relying on socialization alone became controversial.

Social scientists began studying gender inequality beyond socialized selves.

Moving beyond gender as an individual trait

As sociologists began to specialize in gender, the focus on how individuals internalized

gender was problematized. There were two very different theoretical alternatives developed within a sociological framework to move the analysis of gender beyond a focus on

individuals: those who worked in an interactionist tradition, a framework which came to

be known as ‘doing gender,’ and those who were based in more inequality literatures, the

new ‘structuralists’ (see Figure 4). In 1987, West and Zimmerman published their classic

article arguing that gender is something we are held morally accountable to perform,

something we do, not something we are. They founded the ‘doing gender’ paradigm. In

1977, Kanter’s book Men and Women of the Corporation was perhaps the first application of the new structuralism (Bielby and Baron, 1986) to gender. Kanter’s case study

provided evidence that organizational structures in the form of unequal opportunity,

power, and tokenism were at the core of gender inequality, not the differential behavioral

patterns or personalities of women and men as individuals. These two research trajectories developed independently, but eventually came to be tested against one another,

Risman and Davis

739

with complex and contradictory results. We trace the development of each tradition

below.

The new structuralist framework for gender

Kanter’s (1977) research showed that workers who held positions with less formal power

and fewer opportunities for mobility were less motivated and ambitious at work, less

perceived to be leadership material, and more controlling autocratic bosses when they

did enter the ranks of management. Because women and men of color were then overwhelmingly in positions with limited power and opportunity, they were seen as inferior

leaders. When women and men of color were in leadership positions, they were also

usually tokens, and the imbalanced sex and race ratios in their workplaces meant they

faced far greater scrutiny, leading to role encapsulation and extra negative consequences

of scrutiny. Kanter suggested that those women and men of color who made it to management embodied the leadership style of bosses with little power and opportunity for

advancement themselves. The evidence suggested that white majority men who were in

positions with little upward mobility and low organizational power also fulfilled the

stereotype of the micro-managing female boss. Kanter’s case study suggested that apparent sex differences in leadership style represented women’s disadvantaged organizational roles, not their personalities.

The new structuralism soon came to research on explanations for women’s roles in

families. In a study based on life histories of baby boom American women, Gerson’s

Hard Choices (1985) found similarly that women’s socialization and adolescent preferences did not predict their strategy for balancing work and family commitments. The

best explanations for whether women ‘chose’ domestic or work-focused lives were marital stability and success in the labor force. Once again, the structural conditions of everyday life proved more important than feminine selves. In a massive meta-analysis of the

sex differences research on both public and private spheres, Epstein concluded that most

of the differences between men and women were the result of their social roles and societal expectations, and were really Deceptive Distinctions (1988). Epstein argued, as did

Kanter before her, that if men and women were given the same opportunities and constraints, the differences between them would vanish. The structuralist argument is similar

to the argument in Tilly’s theory presented in Durable Inequality (1999), where the

dynamics between superordinate and subordinate groups are based on power and numerical domination, and not the cultural characteristics of either group. Here, gender is

defined more as deception than reality. The core of a structuralist argument is genderneutral; the same structural conditions create behavior, regardless of whether men or

women are filling the social roles.

In a review of research that explicitly tested structuralist theories about workplaces by

studying men in female-dominated occupations, Zimmer (1988) found that there was

more to gender inequality in organizations than the structural placement of women as a

subordinate group. The gender-neutral component of structuralism simply did not have

empirical support. When men were the minority group, they were not marginalized into

less powerful positions with less mobility. Instead, men benefit from occupying a token

status within female-dominated occupations and ride glass escalators to the top. Williams

740

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

(1992), for example, found that token white men in female nursing quickly became

administrators and were more likely to socialize with doctors then other nurses. More

recent research suggests that this glass escalator may only be available to white men,

while men of color in female-dominated positions get left at the ground floor (Wingfield,

2009). Thus, racial privilege is embedded as a status characteristic of employees just as

is gender. Neither gender- nor race-neutral theories of structuralism receive empirical

support (Bonilla-Silva, 1997; Risman, 2004).

Research about women and men’s roles in families has also been used to test the

importance of structural factors to explain gendered behavior. Nearly all the quantitative

research suggests that women continue to do more family labor than their husbands, even

when they work outside the home as many hours per week and earn equivalent salaries

(Bianchi et al., 2000; Bittman et al., 2003). Tichenor’s (2005) qualitative research shows

strong empirical evidence that high earning wives, even those who earn significantly

more than their husbands, are compelled by the cultural logic of intensive mothering to

shoulder more of the family work. While Sullivan (2006) and Kan et al. (2011) show

convincingly that trends have changed over time, with men doing more family labor each

decade cross-nationally, no one disputes that gender still trumps the structural material

variables of time and economic dependency when it comes to housework and care work

(Risman, 2011).

Doing gender framework

During the same era, but on a parallel track, the importance of symbolic interactionism for

the understanding of gender became clear. In 1987, West and Zimmerman published their

classic article in which they argued that gender is something we are held morally accountable to perform, something we do more then something we are. West and Zimmerman

(1987) distinguished sex, sex category, and gender from one another in a way that illustrated the importance of the performative link between bodies and gender. An individual’s

sex is determined through societally defined agreed upon biological distinctions, usually

at birth. Sex category, on the other hand, is used as a proxy for sex but depends upon performing gender appropriately to be accepted as claimed. Sex category does not always

coincide with one’s biological sex, as it is established through ‘required identificatory

displays’ (West and Zimmerman, 1987: 127). These required displays include, but are not

limited to, sex-specific clothing, hairstyles, and appropriate behavior. That is, to claim a

sex category, women and men have to do gender. By conceptualizing gender as something

that we do, West and Zimmerman (1987) were able to draw attention to the ways in which

behaviors are enforced, constrained, and policed during social interaction.

West and Zimmerman’s (1987) doing gender perspective is similar in its deconstructionist tendency to Judith Butler’s theory of gender (Butler, 1990, 2004). West and

Zimmerman’s (1987) doing gender perspective and Butler’s (1990, 2004) conceptualization of gender performativity share the focus on creation of gender by the activity of the

actor, they differ on the ontological reality of the possibility of a self, outside the discursive realm (see Green, 2007). Social scientists study the flexibility of the self, the constructivist self, but presume some version of a self comes to exist, if only temporarily. On

the other hand, Butler (1990, 2004), a philosopher and queer theorist, deconstructs the

Risman and Davis

741

possibility of even a temporary self outside of discourse. In this queer theory tradition,

the self is more an imaginary figment then a constructed, even temporary, self-identity.

Queer theorists such as Butler (1990, 2004) have added to the discussion of ‘doing gender’ in critical ways, helping to sharpen the focus on performativity.

The ‘doing gender’ framework has become perhaps the most common perspective in

contemporary sociological research. A 2011 citation search indicates the article has been

cited 4195 times since its publication. Qualitative research has provided a great deal of

evidence that women and men do gender, but do so dramatically differently across time,

space, ethnicity, and social institution. Households have become ‘gender factories’ (Berk,

1985) where women do more of the labor because by doing so, they are doing gender

itself. Connell (1995) shows clearly that there are numerous ‘masculinities’ that exist

simultaneously, although one is most rewarded and performed by the most privileged

men. Similarly, researchers have described a myriad of ways that girls and women do

femininity, from ‘intensive mothering’ (Hays, 1998; Lareau, 2003) to ‘femme’ lesbians

appropriating traditional emphasized symbols of womanhood such as heels and hose

(Levitt et al., 2003). Lorber’s (1994) meta-review of gender research throughout the 20th

century provides a dazzling overview of the quantity of research showing how gender is

performed and then institutionalized into society.

Acker (1990, 1992) transformed gender theorizing when she expanded a ‘doing gender’ argument to organizations. Instead of gender-neutral organizational structure, she

found gender deeply embedded in organizational structure. While Kanter (1977) conceptualized gender inequality as the result of women occupying lower positions in an organization, Acker (1990, 1992) argued the very definition of jobs and organizational

hierarchies are gendered, constructed to advantage men or others who have no caretaking

responsibilities. Acker writes, ‘The term “gendered institutions” means that gender is

present in the processes, practices, images, and ideologies, and distributions of power in

the various sectors of social life’ (1992: 567). Acker contended there is little place for

those (usually women) who hold positions as caretakers outside the workplace to fulfill

elite ranks of modern corporations, as it is the abstract worker who ‘is actually a man,

and it is the man’s body … that pervades work and organizational processes’ (Acker,

1990: 152). While creating opportunity for women to enter the workplace may increase

their overall numbers within an organization, Acker argues it will not confront the underlying sexism that blocks women’s overall mobility within organizations. Others have

furthered this argument by showing that elite and privileged women may indeed enter

masculine spaces by outsourcing their domestic labor to other less privileged women

(MacDonald, 2011; Nakano Glenn, 2010).

While consensus exists that ‘doing gender’ is ubiquitous, recently there has been criticism of how what counts as evidence of ‘doing gender’ has become. Deutsch (2007)

suggested that when researchers find unexpected behaviors, rather than question whether

gender is being ‘undone,’ they simply claim to discover different femininities and masculinities. Risman (2009) builds upon this critique by suggesting that the ubiquitous

usage of ‘doing gender’ creates conceptual confusion as we study a world that is indeed

changing. Both Deutsch (2007) and Risman (2009) suggest that researchers must know

what they are looking for when studying gendered behavior and be willing and ready to

admit it when they do not find it. If researchers take the search for ‘undoing gender’ as

742

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

seriously as the search for ‘doing it,’ then they will notice when changes actually happen,

when boys and girls, men and women, do not follow traditional scripts, whatever these

are in their own cultural setting (Deutsch, 2007; Risman, 2009).

Intersectional and integrative theories

During the 1980s and 1990s, feminists of color were also theorizing about gender as

something beyond a personality characteristic, with a focus on how masculinity, femininity, and gender relations varied across ethnic communities, and national boundaries.

For example, Patricia Hill Collins (1990), Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), Deborah King

(1988), and Audre Lorde (1984) conceptualized gender as an axis of oppression intersecting with other axes of oppression including race, sexuality, nationality, ability, religion, etc. Feminists of color were critical of gender theory that positioned white western

women as the ‘universal female subject’ and race theories for situating men of color as

the ‘universal racial subject.’ Nakano Glenn (1999) describes the situation as one where

‘[w]omen of color were left out of both narratives, rendered invisible both as racial and

gendered subjects’ (Nakano-Glenn, 1999: 3). Mohanty (2003) was similarly critical, suggesting that feminist scholars were too often focused on the white western world instead

of integrating a global perspective into their theories, and when such was attempted it

was done in an additive rather than comparative fashion.

Although scholars labeled the experience, and ultimately the theory, of being

oppressed in multiple ways and in multiple dimensions differently (e.g., Collins, 1990;

Crenshaw, 1989; Harris, 1990; Mohanty, 2003; Nakano Glenn, 1999), they shared a goal

of highlighting how social location within gender, race, sexuality, class, nationality, and

age must be understood interactively as opposed to studied as distinct domains of life. In

Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins (1990) builds on earlier intersectionality

work (e.g., Crenshaw, 1989; Lorde, 1984) by arguing for the ‘matrix of domination’ as a

concept that seeks to understand ‘how … intersecting oppressions are actually organized’ to oppress marginalized individuals (2000: 16). Hill Collins moves beyond

acknowledging various axes of oppression by challenging us to understand how individuals situated in various locations throughout the matrix of domination are differently

oppressed. Building on this tradition and the work of Judith Butler (1990) discussed

earlier, Ingraham (1994: 203) claims that feminist sociology is ‘losing its conceptual and

political edge’ to the humanities for ignoring sexuality in studies of gender. Instead of

centering sexuality as an institutional source of oppression, Ingraham contends feminist

sociologists reside in a ‘heterosexual imaginary’ where gender is studied separately from

sexuality in a way that ‘conceals the operation of heterosexuality in structuring gender

[by closing off] any critical analysis of heterosexuality as an organizing institution’

(1994: 203–204).

Toward the end of the 20th century, the conceptualization of gender as a stratification

system that exists outside of individual characteristics (e.g., Connell, 1987; Lorber, 1994;

Martin, 2004; Risman, 1998, 2004) and varies along other axes of inequality (e.g.,

Collins, 1990; Crenshaw, 1989; Ingraham, 1994; Harris, 1990; Mohanty, 2003; Nakano

Glenn, 1992, 1999) became the new consensus. Most social scientists embraced the definition of gender as not merely a personality trait, but as a social system that restricts and

Risman and Davis

743

encourages patterned behavior. We briefly discuss three of these leading multidimensional gender frameworks (e.g., Lorber, 1994; Martin, 2004; Risman, 2004) below before

focusing on the one we have been developing over the last decade.

In 1994, Lorber argued that gender is a social institution. She located its existence in

both micro- and macro-level politics that effect domestic work, family life, and the workplace. Lorber concluded that gender, as a historically established institution, has created

and perpetuated differences between men and women and exists to justify inequality.

Although Lorber (2005) presents gender as a social institution, she believes it can be

challenged and deconstructed. She challenges us to eliminate gender inequality, but also

acknowledges that ‘society has to be structured for equality’ (Lorber, 1994: 294). Gender

equality can only occur, Lorber (1994, 2005) maintains, when all individuals are guaranteed equal access to valued resources and society is de-gendered.

Building on Lorber’s (1994) conceptualization of gender as a social institution, Martin

(2004) presents criteria that characterize institutions to show that gender meets each one.

Martin maintains that institutions include, involve, and/or are capable of: (1) collectivities of people; (2) existence across time and space; (3) reoccurring social practices; (4)

constraining and facilitating behavior; (5) expectations, rules/norms, and procedures; (6)

exist because of active embodied agents; (7) meaningful and embedded throughout participants’ identities; (8) include a legitimating ideology; (9) are infiltrated with conflict;

(10) repeatedly change; (11) are controlled by power; and (12) are inseparable from

individuals. Martin concludes that gender meets each of these criteria, and thus suggests

that gender should be studied like other social institutions, such as the family and

religion.

Risman (1998, 2004) builds on both of these theories, as she offers a broader and

more theoretically diverse framework by conceptualizing gender as a social structure

that has consequences at the individual, interactional, and institutional levels of analysis.

Below we argue that this theoretical framework holds promise for the future. In the rest

of this article, we outline our argument in some detail.

Gender as a social structure

Just as every society has a political and economic structure, so, too, does every society

have a gender structure (Risman, 1998, 2004). While the language of structure is useful,

it is not ideal because no definition of the term ‘structure’ is widely shared. Still, all

structural theories share the presumption that social structures exist outside individual

desires or motives and that social structures at least partially explain human action

(Smelser, 1988). Beyond that, consensus dissipates. We use Giddens’s (1984) structuration theory to help conceptualize gender as a structure that creates stratification, with an

emphasis on the recursive relationship between structure and individuals. Like Giddens,

we embrace the transformative power of human action. Social structures not only act on

people; people act on social structures. Indeed, social structures are created not by mysterious forces, but by human action. We are therefore interested in why actors choose

their acts, not only their verbal justifications, but also the part of life so routine and so

taken-for-granted that actors often cannot articulate, nor do they even consider, why

they act.

744

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

In order to present how we use structuration theory to conceptualize gender as a structure, it is useful to compare structuralist theories and voluntarist ones to Giddens’s structuration theory (Bryant and Jary, 2003). Structuralist theories generally assume that

structures and cultures determine, shape, or heavily constrain human action. We previously discussed both Kanter’s (1977) and Epstein’s (1988) theories for gender as examples of such structuralist theories. Choices in these models are illusory, marginal, or

trivial. Actors are victims of circumstances. On the other hand, in voluntaristic theories,

for example, rational choice theory, structures are the easily constructed products of

totally free agents (Coleman, 1994). Actors make real choices and determine their life

outcomes, and the collective social structure. In many ways, Giddens’s structuration

theory combines structural and voluntaristic frameworks (Bryant and Jary, 2003) and we

incorporate this dialectical paradigm into our argument. Structure is the medium and the

outcome of conduct which recursively organize it. Actors are knowledgeable and competent agents who reflexively monitor actions. The taken-for-granted and often unacknowledged conditions of action do shape behavior, but do so as human beings reflexively

monitor the intended and unintended consequences of their action, sometimes reifying

the structure, and sometimes changing it. It is this definition of ‘structure’ that is most

useful for conceptualizing gender as a social structure.

This conceptualization of structure embeds cultural concepts within it as the nonreflexive habituated rules, patterns, and beliefs which organize much of human life. The

taken-for-granted or cognitive images that belong to the situational context (not only or

necessarily to the actor’s personality) are the cultural aspect of the gender structure, the

interactional expectations that each of us meet in every social encounter. Connell (1987)

applied Giddens’s (1984) concern with social structure as both constrained and created

by action in her treatise on gender and power (see particularly Chapter 5). In her analysis,

structure constrains action, yet ‘since human action involves free invention … and is

reflexive, practice can be turned against what constrains it; so structure can deliberately

be the object of practice’ (Connell, 1987: 95). Action may turn against structure but can

never escape it. We must pay attention both to how structure shapes individual choice

and social interaction and how human agency creates, sustains, and modifies current

structure. Action itself may change the immediate or future context.

A theory of gender as a social structure integrates this notion of reflexive causality

and cultural meanings with attention to multiple levels of analysis. Gender is deeply

embedded as a basis for stratification not just in our personalities, our cultural rules, or

institutions, but in all these, and in complicated ways. The gender structure differentiates

opportunities and constraints based on sex category and thus has consequences on three

dimensions: (1) at the individual level, for the development of gendered selves; (2) during interaction as men and women face different cultural expectations even when they

fill the identical structural positions; and (3) in institutional domains where both cultural

logics and explicit regulations regarding resource distribution and material goods are

gender specific (see Figure 5).

When we are concerned with the means by which individuals come to have a preference to do gender, we should focus on how identities are constructed through early childhood development, explicit socialization, modeling, and adult experiences, paying close

attention to the internalization of social mores. To the extent that women and men choose

Risman and Davis

745

Figure 5. Gender as structure.

See Risman (1998: 29).

to do gender-typical behavior across their own social roles and over the life-cycle, we

must focus on such individual explanations. Indeed, much attention has already been

given to gender socialization and the individualist presumptions for gender. The earliest

and perhaps most commonly referred to explanations in popular culture depend on sex

role training, teaching boys and girls their culturally appropriate roles. Bem (1993)

writes elegantly about the enculturation that creates cultural natives, embedding the logic

of essential gender differences and andocentrist beliefs as internalized aspects of young

children’s selves. She suggests that gender schemas depend both on gender relations in

contemporary society and the socialization practices of parents themselves. As discussed

above, such individualist research and theory has been important since the beginning of

social scientific attention to gender as ‘sex roles.’ In this integrative framework, we suggest that continued attention is necessary to the construction of the self, both the means

by which socialization leads to internalized predispositions, and how once selves are

adopted, people use identity work to maintain behaviors that bolster their sense of selves

(Schwalbe et al., 2000). It is clearly the case that women and men internalize norms and

become gendered cultural natives. The important lesson from the accumulation of

research over the 20th century is not that culture doesn’t matter for individual selves, but

that socialization and identity work alone do not explain all of gender stratification.

Social psychology also offers us a glimpse of possibilities for understanding how

inequality is reconstituted in daily interaction. Gender organizes the interactional expectations that every human being meets often in every moment of life. Ridgeway and her

colleagues (Ridgeway, 1991, 1997, 2001, 2011; Ridgeway and Correll, 2004) show convincingly that the status expectations attached to gender and race categories are crosssituational. These expectations can be thought of as one of the engines that recreate

inequality even in novel situations where there is no other reason to expect male or white

privilege to emerge. In a sexist and racist society, women and all persons of color are

746

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

Figure 6. Dimensions of gender structure, by illustrative social processes.

See Risman (2004: 437).

expected to have less to contribute to task performances than are white men, unless they

have some externally validated source of prestige. Women are expected to be more

empathetic and nurturing, men to be more efficacious and agentic. Status expectations

create a cognitive bias toward privileging men with agency and women with nurturance

(Ridgeway, 2011). Cognitive bias of this sort helps to explain the reproduction of gender

inequality in everyday life.

Gender structures social life not only by creating gendered selves and cultural expectations that shape interactions, but also by organizing social institutions and organizations (see Figure 6). As Acker (1990) and Martin (2004) have shown, economic

organizations embed gender meanings in the definition of jobs and positions. Any organization that presumes valued workers are available 50 weeks a year, at least 40 hours a

week, for decades on end, presumes that such workers have no practical or moral responsibility for taking care of anyone but themselves. The industrial and post-industrial economic structure presumes workers have wives, or do not need them. In many societies,

the legal system also presumes women and men have distinct rights and responsibilities.

For example, some western governments allow for different retirement ages for women

and men, thus building gender into legislative bureaucracy. It is clear, however, that

much has begun to change in western democracies, as laws move toward gender-neutrality.

Even when the actual formal rules and regulations begin to change, however, whether by

government, courts, religion, higher education, or organizational rules, the cultural logic

often remains, hiding patriarchy in gender-neutral formal law (Williams, 2001). Within

the institutional domain, the distributions of both actual resources which privilege men

and ideological androcentrism often outlive formal legislative male privilege.

The multidimensionality of gender structure theory has already begun to provide a

useful framework for empirical research (Armstrong et al., 2006; Banerjee, 2010; Davis,

2011; Davis and Risman, 2009; Legerski and Cornwall, 2010). Within gender structure

theory, research can explore the dialectical relationships between the individual, interactional, and institutional levels. When does an individual choice of gendered options

reflect internalized femininity or masculinity, and when do the expectational pressures of

Risman and Davis

747

others prevail? How does the behavior chosen by individuals impact the expectations of

others, and eventually institutions themselves? When are gendered choices the only ones

even imagined? And do institutional changes affect individual imaginations of the possible? Can we study when we are doing gender and recreating inequality without intent?

And what happens to interactional dynamics and male-dominated institutions when

actors reflexively rebel? Can we explore when people refuse to do gender whether they

‘undo’ it or simply do gender differently, forging alternative masculinities and femininities that are then internalized as identities? And when does changing social policy effectively change the expectations people hold for others, or for themselves? Future research

should follow the causal relationships, as dominoes, to see when, and in what contexts,

change begets change, and when it does not. These are some of the possibilities fostered

by using gender as a social structure to design research.

Conclusion

In summary, gender inequality is produced, maintained, and reproduced at each level of

social analysis (individual, interactional, and institutional). At the individual level, the

development of gendered selves emerges through the internalization of either a male or

female identity. There is no reason to deny the influence of bodies, by shape or size, on

how selves develop. The debates about the influence of biology on possible predisposition of personality solidly falls within such analyses (Miller and Costello, 2001; Risman,

2001; Udry, 2000). The enculturation creates feminine women and masculine men, but

not entirely, nor consistently, nor always. The interactional dimension of the gender

structure involves the sex categorization that triggers stereotypes about women and men.

These involve cultural logics that shape what we expect from each other, and ourselves.

The institutional dimension of the gender structure perpetuates gender inequality through

a variety of organizational processes, explicitly sexist or newly gender-neutral, but with

cultural logics still embedded within them.

Theoretical understandings of gender have changed dramatically since the birth of

serious attention in the last century. First, research was limited primarily to the biological

sciences (Evans, 1939; Frank, 1929; Laqueur et al., 1927; Parkes, 1938; Phoenix et al.,

1959; Siebke, 1931; Young et al., 1965; Zondek, 1934a, 1934b). While the biological

sciences continue to contribute to the vibrant collection of studies on gender (Arnold and

Gorski, 1984; Brizendine, 2006; Cahill, 2003; Collaer and Hines, 1995; Cooke et al.,

1998; Holterhus et al., 2009; Lippa, 2005), we have also seen the explosive growth and

development of social scientific research and theory. The cumulative research traditions

started with a focus primarily on the individual level of analysis of gendered selves, and

then expanded to include concerns with the structure of organizations and the interactional processes that create inequality. We have offered a synopsis of our contribution to

the contemporary theory, conceptualizing gender as a social structure (Risman, 1998,

2004) integrating complex causal arguments across individual, interactional, and institutional levels. We have focused primarily on the development of gender studies within the

US and we look forward to incorporating more information about how sex and gender

has evolved in other parts of the world, and with more attention to the state and political

economy.

748

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

There have been dramatic changes in understandings of sex and gender over time.

And while we offer a theory that may be useful for today, we acknowledge that today’s

theoretical frameworks about gender will continue to develop as they are used in research,

tested, supported, or refuted. The most important finding from this meta-review of previous work is that the social scientific understanding about gender continues to be cumulative, building on empirical research which verifies or challenges whatever is today

cutting edge. We hope our article contributes to further revisions and greater knowledge

in an attempt to use scientific inquiry to help create a more just world.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the graduate students at the University of Illinois at Chicago who have taken courses in

sociology of gender, feminist theory, and contemporary sociology with the authors and have contributed to debates on these ideas. The senior author also thanks Vincent Roscigno who invited her to be

a plenary speaker at the 2011 Southern Sociological Society meetings and prompted the first draft of

this article, and the thoughtful audience critique at the meeting. We also thank the Center for Gender

Studies at the University of Trento for inviting the senior author to present this work as a plenary in

February 2012 at Attraverso i Confini del Genere. We are grateful to Rachel Allison, Pallavi Banerjee,

Amy Brainer, and Irene Padavic for their comments on an earlier draft of the article. We thank

Suzanne Vromen and Nilda Flores-Gonzalez for their help with translating the abstract into French

and Spanish. The arguments made, including any errors, belong to the authors alone.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or

not-for-profit sectors.

Annotated further reading

Collins PH (1990) Black Feminist Thought. New York: Routledge. In this key work, Patricia Hill

Collins offers a comprehensive understanding of the way in which various axes of inequality

(e.g. race, class, gender, sexuality, and nationality) intersect with one another to form a matrix

of domination that is perpetuated by different domains of power.

Davis G (2011) DSD is a perfectly fine term: Reasserting medical authority through a shift in intersex terminology. In: McGann PJ and Hutson DJ (eds) Sociology of Diagnosis. Bingley, UK:

Emerald, pp. 155–182. In this piece, Georgiann Davis documents how medical professionals

reclaimed jurisdiction over intersexuality by renaming intersex traits as disorders of sex development (DSD). Prior to the DSD diagnostic nomenclature, intersex activists were successfully

framing intersexuality as a social rather than medical problem.

Jordan-Young RM (2010) Brainstorm: The Flaws in the Science of Sex Differences. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press. A soon to be classic book that, through a synthetic analysis,

documents how brain organization research is methodologically flawed because of its reliance

on inconsistent conceptualizations and inadequate measurement.

Lorber J (1994) Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. A now classic text

that analyzes gender as a social institution that permeates all aspects of human life. Lorber

identifies gender inside and outside of our homes through a variety of social structures operating though micro- and macro-level politics. She shows how gender effects domestic work,

family life, and the workplace. Lorber argues that the historically established institution of

gender has created not only differences between men and women but also serious inequality.

The key paradox of gender is that it must be made visible in order for it to be dismantled.

Risman and Davis

749

Ridgeway CL (2011) Framed by Gender: How Gender Inequality Persists in the Modern World.

New York: Oxford University Press. Building on her earlier work that maintains gender is a

primary frame in the organization of social relations, Cecilia Ridgeway theorizes in this book

that status expectations create a cognitive bias toward expecting men to be effective and agentic, and women to be nurturant. She draws on experimental social psychological and sociological evidence to support her theoretical claims.

Risman BJ (2004) Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender and

Society 18(4): 429–451. In this piece, Barbara Risman introduced her theory of gender as a

social structure, with implications beyond the family. She argued that gender should be conceptualized and studied as a social structure with consequences at the individual, interactional,

and institutional levels. Each dimension helps frame the processes by which gender inequality

is produced, maintained, and recreated. The argument from this article has been integrated and

advanced in the current publication.

West C and Zimmerman DH (1987) Doing gender. Gender and Society 1(2): 125–151. This influential piece argues gender is a performance that we are all held morally accountable during social interaction to accomplish. To support this claim, West and Zimmerman distinguish

between sex, sex category, and gender; they argue that we use gender to claim a sex category,

which may or may not be identical to our assigned biological sex.

References

Acker J (1990) Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender and Society

4(2): 139–158.

Acker J (1992) From sex roles to gendered institutions. Contemporary Sociology 21(5): 565–569.

Armstrong EA, Hamilton L and Sweeney B (2006) Sexual assault on campus. Social Problems

53(4): 483–499.

Arnold AP and Gorski RA (1984) Gonadal-steroid induction of structural sex-differences in the

central nervous system. Annual Review of Neuroscience 7: 413–442.

Bandura A and Waters RH (1963) Social Learning and Personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart

and Winston.

Banerjee P (2010) ‘Vegetable visa’: Gender in families of immigrating Indian professionals with

one spouse on dependent visa. In: Annual Meetings of the American Sociological Association

Atlanta, GA.

Bell WB (1916) The Sex Complex: A Study of the Relationship of the Internal Secretions to the Female

Characteristics and Functions in Health and Disease. London: Baillière, Tindall and Cox.

Bem S (1974) The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology 42(2): 65–82.

Bem S (1981) Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review

88: 354–364.

Bem S (1993) The Lenses of Gender: Transforming the Debate on Sexual Inequality. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

Berk SF (1985) The Gender Factory: The Apportionment of Work in American Households. New

York: Plenum Press.

Bianchi SM, Milkie MA, Sayer LC et al. (2000) Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the

gender division of household labor. Social Forces 79(1): 191–228.

Bielby WT and Baron JN (1986) Men and women at work: Sex segregation and statistical

discrimination. American Journal of Sociology 91(4): 759–799.

Bittman M, England P, Folbre N et al. (2003) When does gender trump money? Bargaining and

time in household work. American Journal of Sociology 109(1): 186–214.

750

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

Bonilla-Silva E (1997) Rethinking racism: Towards a structural interpretation. American Sociological

Review 62: 465–480.

Brizendine L (2006) The Female Brain. New York: Morgan Road Books.

Bryant CGA and Jary D (2003) Anthony Giddens. In: Ritzer G (ed.) The Blackwell Companion to

Major Contemporary Social Theorists. Malden, MA: Blackwell, pp. 247–273.

Butler J (1990) Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Butler J (2004) Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

Cahill L (2003) Sex- and hemisphere-related influences on the neurobiology of emotionally influenced memory. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 27(8):

1235–1241.

Chafetz JS (1998) From sex/gender roles to gender stratification: From victim blame to system

blame. In: Myers KA, Anderson CD and Risman BJ (eds) Feminist Foundations: Toward

Transforming Sociology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 159–164.

Choi N and Fuqua DR (2003) The structure of the Bem sex role inventory: A summary report of 23

validation studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement 63: 872–887.

Choi N, Fuqua DR and Newman JL (2008) The Bem sex-role inventory: Continuing theoretical

problems. Educational and Psychological Measurement 68: 881–800.

Coleman JS (1994) Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Collaer ML and Hines M (1995) Human behavioral sex differences: A role for gonadal hormones

during early development? Psychological Bulletin 118(1): 55–107.

Collins PH (1990) Black Feminist Thought. New York: Routledge.

Collins PH (2000) Black Feminist Thought, 2nd edn. New York: Routledge.

Connell RW (1987) Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. Palo Alto, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Connell RW (1995) Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cooke B, Hegstrom CD, Villeneuve LS et al. (1998) Sexual differentiation of the vertebrate brain:

Principles and mechanisms. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 19(4): 323–362.

Crenshaw K (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of

antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago

Legal Forum 139–167.

David K, Freud J and De Jongh SE (1934) Conditions of hypertrophy of seminal vesicles in rats II:

The effect of derivatives of oestrone (menoformon). Biochemical Journal 28(2): 1360–1367.

Davis G (2011) ‘DSD is a perfectly fine term’: Reasserting medical authority through a shift in

intersex ierminology. In: McGann PJ and Hutson DJ (eds) Sociology of Diagnosis. Bingley:

Emerald, pp. 155–182.

Davis G and Risman BJ (2009) Beyond sex, beyond gender: A gender structure analysis of the intersex rights movement. In: Annual Meetings of the Midwest Sociological Society, Des Moines, IA.

Deutsch FM (2007) Undoing gender. Gender and Society 21(1): 106–127.

Diamond M (2009) Clinical implications of the organizational and activational effects of hormones. Hormones and Behaviors 55(5): 621–632.

Edwards AL and Ashworth CD (1977) A replication study of item selection for the Bem sex role

inventory. Applied Psychological Measurement 1(4): 501–507.

England P, Allison P, Li S et al. (2007) Why are some academic fields tipping toward female?

The sex composition of U.S. fields of doctoral degree receipt, 1971–2002. Sociology of

Education 80(1): 23–42.

Epstein CF (1988) Deceptive Distinctions: Sex, Gender, and the Social Order. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

Epstein S (1996) Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Risman and Davis

751

Evans HM (1939) Endocrine glands: Gonads, pituitary and adrenals. Annual Review of Physiology

1: 577–652.

Fausto-Sterling A (2000) Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New

York: Basic Books.

Ferree MM (1990) Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research. Journal of Marriage

and the Family 53(4): 866–884.

Ferree MM and Hall EJ (1996) Rethinking stratification from a feminist perspective: Gender, race,

and class in mainstream textbooks. American Sociological Review 61(6): 929–950.

Frank RT (1929) The Female Sex Hormone. Baltimore, MD: Charles C Thomas.

Gerson K (1985) Hard Choices: How Women Decide about Work, Career, and Motherhood.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Giddens A (1984) The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Gill S, Stockard J, Johnson M et al. (1987) Measuring gender differences: The expressive dimension and critique of androgyny scales. Sex Roles 17(7/8): 375–400.

Green AI (2007) Queer theory and sociology: Locating the subject and the self in sexuality studies.

Sociological Theory 25(1): 26–45.

Harris A (1990) Race and essentialism in feminist legal theory. Stanford Law Review 42: 581–616.

Hays S (1998) The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press.

Hoffman RM and Borders LD (2001) Twenty-five years after the Bem sex role inventory: A reassessment and new issues regarding classification variability. Measurement and Evaluation in

Counseling and Development 34: 39–55.

Holterhus PM, Bebermeier JH, Werner R et al. (2009) Disorders of sex development expose transcriptional autonomy of genetic sex and androgen-programmed hormonal sex in human blood

leukocytes. BMC Genomics 10: 292.

Hrabovszky Z and Hutson JM (2002) Androgen imprinting of the brain in animal models and

humans with intersex disorders: Review and recommendations. The Journal of Urology

168(5): 2142–2148.

Ingraham C (1994) The heterosexual imaginary: Feminist sociology and theories of gender.

Sociological Theory 12(2): 203–219.

Jordan-Young RM (2010) Brainstorm: The Flaws in the Science of Sex Differences. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Juntti SA, Coats JK and Shah NM (2008) A genetic approach to dissect sexually dimorphic behaviors.

Hormones and Behaviors 53(5): 627–637.

Kan MY, Sullivan O and Gershuny J (2011) Gender convergence in domestic work: Discerning

the effects of interactional and institutional barriers from large-scale data. Sociology 45(2):

234–251.

Kanter RM (1977) Men and Women of the Corporation. New York: Basic Books.

Kennelly I, Merz SN and Lorber J (2001) What is gender? American Sociological Review 66(4):

598–605.

Kimmel MS (2008) The Gendered Society, 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

King DK (1988) Multiple jeopardy, multiple consciousness: The context of a black feminist ideology. Signs 14(1): 42–72.

Kohlberg L (1966) A cognitive-developmental analysis of children’s sex-role concepts and

attitudes. In: Maccoby EE (ed.) The Development of Sex Differences. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

Laqueur E, Dingemanse E, Hart PC et al. (1927) Female sex hormone in urine of men. Klinische

Wochenschrift 6(1): 859.

752

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

Lareau A (2003) Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Legerski EM and Cornwall M (2010) Working-class job loss, gender and the negotiation of household labor. Gender and Society 24(4): 447–474.

Lever J (1974) Games Children Play: Sex Differences and the Development of Role Skills. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Levitt HM, Gerrish EA and Hiestand KR (2003) The misunderstood gender: A model of modern

femme identity. Sex Roles 48(3/4): 99–113.

Lillie FR (1939) Biological introduction. In: Allen E (ed.) Sex and Internal Secretions, 2nd edn.

Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

Lippa RA (2005) Gender, Nature, and Nurture. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Locksley A and Colten ME (1979) Psychological androgyny: A case of mistaken identity?

Personality and Social Psychology 37(6): 1017–1031.

Lopata HZ and Thorne B (1978) On the term sex roles. Signs 3(3): 718–721.

Lorber J (1994) Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lorber J (2005) Breaking the Bowls: Degendering and Feminist Change. New York: WW

Norton.

Lorde A (1984) Sister Outsider. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press Feminist Series.

MacDonald C (2011) Shadow Mothers: Nannies, Au Pairs, and the Micropolitics of Mothering.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Martin PY (2004) Gender as social institution. Social Forces 82(4): 1249–1273.

Miller EM and Costello C (2001) The limits of biological determinism. American Sociological

Review 66(4): 592–598.

Mohanty CT (2003) Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Nakano Glenn E (1992) From servitude to service work: Historical continuities in the racial division of paid reproductive labor. Signs 18(1): 1–43.

Nakano Glenn E (1999) The social construction and institutionalization of gender and race: An

integrative framework. In: Ferree MM, Lober J and Hess B (eds) The Gender Lens: Revisioning

Gender. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Nakano Glenn E (2010) Forced to Care: Coercion and Caregiving in America. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Oudshoorn N (1994) Beyond the Natural Body: An Archeology of Sex Hormones. London:

Routledge.

Parkes AS (1938) Terminology of sex hormones. Nature 141: 12.

Parsons T and Bales RF (1955) Family, Socialization, and Interaction Process. New York: Free

Press.

Pedhazur EJ and Tetenbaum TJ (1979) Bem sex role inventory: A theoretical and methodological

critique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37(6): 996–1016.

Phoenix CH, Goy RW, Gerall AA et al. (1959) Organizing action of prenatally administered

testosterone propionate on the tissues medicating mating behavior in the female guinea pig.

Endocrinology 65(3): 369–382.

Ridgeway CL (1991) The social construction of status value: Gender and other nominal characteristics. Social Forces 70(2): 367–386.

Ridgeway CL (1997) Interaction and the conservation of gender inequality: Considering

Employment. American Sociological Review 62(2): 218–235.

Ridgeway CL (2001) Gender, status, and leadership. Journal of Social Issues 57(4): 637–655.

Ridgeway CL (2011) Framed by Gender: How Gender Inequality Persists in the Modern World.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Risman and Davis

753

Ridgeway CL and Correll SJ (2004) Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on

gender beliefs and social relations. Gender and Society 18(4): 510–531.

Risman BJ (1998) Gender Vertigo: American Families in Transition. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

Risman BJ (2001) Calling the bluff of value-free science. American Sociological Review 66(4):

605–611.

Risman BJ (2004) Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender and Society

18(4): 429–451.

Risman BJ (2009) From doing to undoing: Gender as we know it. Gender and Society 23(1):

81–84.

Risman BJ (2011) Gender as structure or trump card? Journal of Family Theory and Review 3:

18–22.

Rossi A (1983) Beyond the gender gap: Women’s bid for political power. Social Science Quarterly

64(4): 718–733.

Schwalbe M, Holden D, Schrock D et al. (2000) Generic processes in the reproduction of inequality: An interactionist analysis. Social Forces 79(2): 419–542.

Siebke H (1931) Presence of androkinin in female organism. Archiv für Gynaekologie 146: 417–

462.

Smelser NJ (1988) Social structure. In: Handbook of Sociology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp.

103–129.

Spence JT, Helmreich RL and Holahan CK (1975a) Negative and positive components of psychological masculinity and femininity and their relationships to self-reports of neurotic and acting

out behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37(10): 1673–1682.

Spence JT, Helmreich RL and Stapp J (1975b) Ratings of self and peers on sex role attributes

and their relation to self-esteem and conceptions of masculinity and femininity. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology 32(1): 29–39.

Stockard J and Johnson MM (1980) Sex Roles: Sex Inequality and Sex Role Development.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sullivan O (2006) Changing Gender Relations, Changing Families: Tracing the Pace of Change

Over Time. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Taylor MC and Hall JA (1982) Psychological androgyny: Theories, methods, and conclusions.

Psychological Bulletin 92(2): 347–366.

Terman L and Miles C (1936) Sex and Personality: Studies in Masculinity and Femininity. New

York: McGraw Hill.

Tichenor V (2005) Maintaining men’s dominance: Negotiating identity and power when she earns

more. Sex Roles 53(3/4): 191–205.

Tilly C (1999) Durable Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Udry R (2000) Biological limits of gender construction. American Sociological Review 65(3):

443–457.

Weitzman LJ (1979) Sex Role Socialization: A Focus on Women. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield.

Weitzman LJ, Eifler D, Hokada E et al. (1972) Sex-role socialization in picture books for preschool children. American Journal of Sociology 77(6): 1125–1150.

West C and Zimmerman DH (1987) Doing gender. Gender and Society 1(2): 125-151.

White MS (1979) Measuring androgyny in adulthood. Psychology of Women Quarterly 3(3):

293–307.

Williams C (1992) The glass escalator: Hidden advantages for men in the ‘female’ professions.

Social Problems. 39(3): 253–267.

Williams J (2001) Unbending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What to Do About It.

New York: Oxford University Press.

754

Current Sociology Review 61(5-6)

Wingfield AH (2009) Racializing the glass escalator. Gender and Society 23(1): 5–26.

Young WC, Goy RW and Phoenix CH (1965) Hormones and sexual behavior. In: Money J (ed.)

Sex Research: New Developments. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Zelditch M (1955) Role differentiation in the nuclear family: A comparative study. In: Parsons T

and Bales RF (eds) Family, Socialization, and Interaction Process. Glencoe, IL: pp.

307–352.

Zimmer L (1988) Tokenism and women in the workplace: The limits of gender-neutral theory.

Social Problems 35(1): 64–77.

Zondek BB (1934a) Oestrogenic hormone in the urine of the stallion. Nature 133: 494.

Zondek BB (1934b) Mass excretion of oestrogenic hormone in the urine of the stallion. Nature

133: 209–210.

Author biographies

Barbara Risman is Professor and Head of the Department of Sociology at the University of Illinois

at Chicago. She is the author of Gender Vertigo: American Families in Transition (Yale University

Press, 1998), Families As They Really Are (Norton, 2010), and over two dozen journal articles in

venues including American Sociological Review, Gender and Society, and Journal of Marriage

and the Family. She has been editor of the journal Contemporary Sociology, and is currently one

of the editors of a book series, The Gender Lens, a feminist transformation project for the discipline of sociology.

Georgiann Davis is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Southern Illinois University at

Edwardsville. Her research interests center on the social construction of medical knowledge, specifically how diagnoses are defined and experienced through a gendered framework by medical

professionals, patients, and their families. She is currently studying intersexuality and the intersex

rights movement.

Résumé

Cet article se propose deux buts principaux, une histoire intellectuelle du genre

comme concept et une proposition de cadre conceptuel pour faire avancer la théorie

et la recherche sur le genre considéré comme structure de stratification. Notre

premier objectif est de retracer le développement conceptuel de l’étude du sexe et

du genre depuis le début du 20ème siècle à nos jours. Nous abordons la question du

point de vue de la sociologie féministe avec une préoccupation particulière pour le

pouvoir et l’inégalité. Dans une perspective moderniste, nous cherchons à montrer

comment la théorie et la recherche se construisent de manière cumulative, sur la base

d’études empiriques qui défendent et parfois contredisent les théories actuelles et

qui conduisent à la création de nouvelles théories. Dans une contribution théorique,

nous définissons le genre comme une structure sociale, comme un moyen d’intégrer

la grande variété des résultats de recherche empirique sur les explications causales

et les conséquences du genre. Notre cadre théorique aborde les différences et les

similitudes entre femmes et hommes en tant qu’individus, la permanence et l’évolution

des attentes envers l’autre sexe au cours des interactions sociales et les mécanismes

à l’oeuvre pour intégrer les sexes dans la logique des institutions sociales et des

organisations. A chaque niveau d’analyse, nous nous intéressons à l’organisation de la

vie sociale et aux logiques culturelles qui accompagnent de tels motifs

Risman and Davis

755

Mots-clés

Genre, sexe, stratification, structure par sexe

Resumen

Este artículo tiene dos objetivos: una historia intelectual del concepto de género, y

un esbozo del marco que sugerimos para el avance de la teoría e investigación sobre

género, conceptualizado como una estructura de estratificación social. Nuestro primer

objetivo es trazar el desarrollo conceptual del desarrollo de los estudios de sexo y

género a través del siglo XX hasta la actualidad. Será realizado a partir de un punto

de vista sociológico feminista, encuadrando la cuestión con particular preocupación

por el poder y la desigualdad. Utilizamos una perspectiva modernista, mostrando

cómo la teoría y la investigación construida de una manera acumulativa, con estudios

empíricos que a veces sustentan y a veces desafían las teorías actuales, frecuentemente

llevan hacia nuevas teorías. Entonces, ofreceremos nuestra contribución teórica,

encuadrando al género como una estructura social, como un medio de integrar la

amplia variedad de resultados empíricos de investigación sobre explicaciones causales

para y de consecuencias del género. Nuestro marco presta atención a las diferencias

y similitudes entre mujeres y hombres en cuanto individuos, la estabilidad y el cambio

en las expectativas sobre cada sexo durante la interacción social, y los mecanismos por

los cuales el género está incorporado en la lógica de las instituciones y organizaciones

sociales. En cada nivel de análisis, estamos interesadas en la organización de la vida social

y en las lógicas culturales que acompañan dichos patrones.

Palabras clave

Sexo, estratificación, estructura de género